- Home

- Lisa Rochon

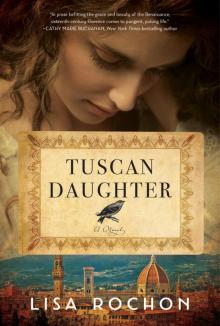

Tuscan Daughter Page 28

Tuscan Daughter Read online

Page 28

Boots on the stone stairs: the sound of Leonardo’s assistants arriving. Machiavelli was right behind them, as if chasing them into the council hall.

“Gentlemen, welcome,” said Soderini. “I’ve waited for this moment for years. Tell me, what work will you be doing?” He was kneading his hands nervously as he looked from Leonardo to the faces of the gathered studio assistants.

It was Giovanni who broke the awkward silence. “As you can see, the rough coat has already been troweled onto the wall. We applied a smooth primer coat of white lead and tapped the outline of the cartoon onto the prepared surface.”

“Yes, very good, very good.” Soderini rubbed his hands together. He looked at the scaffolding that Leonardo had invented, at the trestle tables laden with colors and earthenware vessels for preparing pigments, at the small glass jars filled with linseed oil.

“Leonardo will be painting with oils, working a secco on a dry surface, to honor the encaustic technique of antiquity, which we all admire—”

“Oils?”

“There’s no need to be alarmed,” said Leonardo, understanding that their innovation had set off alarm bells. “We tested our ideas in the studio. I can assure you that painting in this manner produces highly satisfying results, deeper colors and nuances of form without having to rush the process. Fresco means painting fast all the time.”

“Pigment and oils provide all the lush earth tones of—” Giovanni was about to reference The Last Supper, but thought better of referring to that fading experiment.

“But surely there are earthy tones to be found with tempera, letting all the color sink into the wet plaster?” Soderini asked. Machiavelli started to pace in small, tight circles. “Think of all the fresco artists—Masaccio, Fra Angelico, Giotto—they all worked their watercolors into wet surfaces.”

Leonardo raised his eyebrows ever so slightly at his assistants. Soothing the client was a job he loathed. He put a hand on Soderini’s shoulder. “We’ll review all the pouncing of the cartoon on the wall and be painting soon enough. Pure pigments mixed in linseed oil.”

As far as he was concerned, the conversation with the client was completed, and his thoughts wandered. On Saturday he would walk over to Via della Stufa and join Lisa for a celebration. Many moons had passed since they had seen each other, and he needed to apologize for neglecting the portrait. He took off his jacket and rolled up his sleeves. The humidity was thick enough to cut with a dagger. He was sure it would rain.

“How is Michelangelo progressing, do we know?” asked Soderini.

There was another awkward silence. Leonardo brushed back his hair and betrayed no emotion.

“Michelangelo di Buonarroti?” asked Giovanni, as if hearing the name for the first time.

“Very well, I am sure,” said Leonardo smoothly. His shirt was soaked through with sweat, and now he felt light-headed. “I’d wager that we will see the imminent destruction of beauty. Including an army of naked men, his signature.”

Soderini laughed loudly. Then came the slam of a door and the pounding of footsteps across the floor.

“Well spoken, Leonardo. If I may continue your thoughts?” It was Michelangelo, his face swarthy and sun-bronzed. He approached the group with a confident swagger. “They are young men,” he said. “My age,” he added smugly. “And they are caught off guard, barely awake from a long, deep sleep on the banks of the Arno. They’re brave and they’re beautiful and they’re willing to give up their lives in battle.”

“Well, then, let the blood battle begin,” said Machiavelli, clapping his hands as if signaling the start of a horse race.

“Boys, set the scaffold and prepare the linseed oil,” said Leonardo. He rolled up his sleeves.

Michelangelo approached Soderini and bowed. “If it pleases the governor, I would ask that Leonardo be given time to paint his fresco at his leisure. I will follow with my own at a later date.”

Soderini nodded kindly. “Machiavelli? Leonardo? Are we all in agreement?”

They agreed and Michelangelo took his leave.

* * *

Leonardo’s wall painting had begun well enough, despite the extraordinary heat. Standing back in the enormous, airless hall, looking at the lines of the elaborate, entwined horsemen fighting for the flag, Leonardo was almost frightened by what he had created: the horror of war.

The problems began later that week when he started painting the intonaco with the oils. Leonardo had not anticipated the extreme heat. Nobody could have. The oils started sliding down the wall. At first, Ferrando reassured him and pressed more linseed and colored pigments at him. They had to double, then triple, the amount he was accustomed to using. The writhing horses started to melt into the soldiers, the outlines of their faces blurred into unrecognizable shapes.

In the early afternoon, the heavy clouds ripped open and torrential rain pounded down on the rooftops of Florence, punishing the brick cupolone of the Duomo and flooding the streets. A howling wind drove the rain sideways across the city and through the open windows of the council hall. The summer skies had turned dark as night.

“Bring the braziers!” Leonardo shouted over the deafening winds. “Stiffen the oils!” They set three braziers on the floor and waited to see if the oils would dry in place. The wind howled and shutters on the south windows banged open and shut. “Get me a torch,” said Leonardo. “More than one if you can find them.”

Ferrando ran out of the hall and down the spiral stairs, but many precious moments were lost in finding guardsmen, explaining the crisis and securing permission to free one of the torches from the palazzo’s massive stone wall. At last, torch in hand, Leonardo brought the flame close to his wall painting. He had envisioned a mural that would be defined by insane violence, yes, but also a whirling moment of dazzling movement and fantastical allusions to faraway exotic worlds. He was trying desperately to retain the helmet of one of the warriors, designed as an enormous deep-water mollusk and, lower down, a ram’s head as a breastplate. On the soldier’s shoulders were spiky encrustations, as if starfish with a skin of brass tacks had crawled onto them. “Because in war you can believe in anything,” he had once instructed his assistants. Now his dream was slipping away, leaving a trail of humiliation on the wall.

All of the subtle undertones that he had imagined and drawn for more than two years had turned into black smudges.

Salaì rushed into the room carrying another brazier. “Found it in the governor’s private rooms!” But it was too late. Leonardo shook his head. Exhausted, near tears, Giovanni and Ferrando sat on the floor, their backs to the ruined painting. Leonardo walked to the opposite wall and gazed at the massive room, all of him broken. Bowing to his assistants, he walked slowly out of the Palazzo Vecchio, vowing he would never go back.

Chapter 45

It was late in the evening by the time Leonardo reached Via della Stufa. He walked slowly, head down, red paint smeared over his white blouson. At the entrance doors, a night watchman stepped out from the shadows, his hand on his leather scabbard.

“Signore? State your name.”

Leonardo noted the festoons of roses, the gilliflowers and trailing ivy overflowing from the mouths of marble lions. He was at the front entrance of a palazzo, the tall wooden doors finely decorated with bronze foliage. He needed to knock and go in.

“Signore, your name?” The guard had stepped in front of him. He was a big fellow, young, and his unlined face shone with sweat. Despite the afternoon downpour, the humidity had only intensified over the course of the day; now, the nighttime sky had burned to the color of ash.

“My name? That depends on the day, doesn’t it?” The guard stared at him as if he might be confused, or possibly drunk. Leonardo elaborated: “It could be Master of the Arts, or simply Master. It could be Honored Son of Florence—”

“All right, old man, it’s time you went on your way.” The guard gripped Leonardo’s arms and turned him forcefully from the door.

“No, no, I must go in,”

protested Leonardo. The heat was suffocating. “They are expecting me,” he said. “Tell them Leonardo da Vinci is here.”

He saw a hideous face: bulging monster eyes, roiling tongue. Imagined or real? He could hear voices in the distance, his name being whispered. The sight of the grotesquerie sent his mind back to the events of the day. The problems had begun when he’d started painting the richly colored oils over the dry plaster surface. He had not anticipated the extreme heat. The linseed oil seemed bad. Had his supplier cheated him by selling him weak liquid, lacking concentration? The color had slid down the wall. Even his most experienced assistants could do nothing to stiffen the oils and save his wall painting.

He had walked out of the Palazzo Vecchio. He would never go back. In his defeat, he could not stay in Florence—he would find a new patron in another city and grow soft whiling away the years.

A sound of clanging metal and the doors swung open. A bright-faced housemaid peered into the evening, beckoning to Leonardo with both arms. She scowled at the night watchman before shutting the doors with precision. Her leather boots clicked smartly on the marble tile floor.

Inside, the stifling heat dissipated. Leonardo stepped into a cool green oasis afforded by an interior courtyard planted with blossoming night flowers.

“Leonardo, so good of you to come!” It was the silk merchant. Mona Lisa’s husband. “Friends, Leonardo da Vinci has graced our home! He needs no reproduction. I mean, introduction.” The man had obviously had too much to drink.

Leonardo saw women with lead-painted teeth, dressed in brilliant, gaudy colors. They were perched at a grand white marble table and watching him with amusement. Other guests sat below an arbor of blooming roses and linden branches, slapping their legs in laughter with jewel-encrusted hands. The sound of water gushing from a small army of water nymphs overwhelmed his ears. Bankers, lenders and government officials—he recognized many of them—lounged comfortably on long benches of turf.

“Have a seat, dear friend. You don’t mind our rustic experiment?” The silk merchant again, now whispering in his ear. “They call these exedra, the latest furniture art from Venice! Benches made out of grass.”

The sound of laughter was the braying of donkeys.

“Francesco, you are monopolizing our guest.” A gentle hand on his shoulder, the familiar smell of apricot oil. Mona Lisa flitted her fingers at her husband as if to say “Run along.”

“The air is painfully heavy,” she said, handing Leonardo a cup of chilled vin santo and walking him away from the crowded salon.

A servant opened a carved wooden door and they stepped out into the courtyard. The moon hung low in the sky, enormous, a disc of ocher. “I was looking for privacy, but that thing,” she said, gesturing to the sky, “is very demanding.”

“Dazzling to see it. Covered over with water. Maybe they’re golden lakes, reflected back to us like a mirror,” he replied, his voice heavy with exhaustion, bending his hand in a convex shape.

She dared to press her hand against his. They were alone, away from the crowd. “You’ve been working very hard today. I see you are tired.” She led him into the garden and breathed deeply. “Tell me of the fresco, the painting of it at the Palazzo Vecchio. Are you pleased?”

He stepped away from her, unable to speak.

Sensing the mural had not yet achieved his ideal of perfection, she changed the subject. “Beyond your work, my husband has informed me today that your father is very ill.” Francesco and Ser Piero had long contributed to the funds at the Santissima Annunziata; they often met over legal matters.

He nodded and kept looking up at the moon.

“Leonardo, you must go, you must see him on his deathbed. Allow for reconciliation. Perhaps in your heart you will find forgiveness?” She stepped in front of him, forcing him to look at her. “You can’t deny him your presence, his firstborn, in his last hours.”

“I have been an annoyance to him all of my life.”

“I don’t believe that. Why else would he recommend you to Francesco, and the church commissions, if he did not believe in the greatness of your talent?”

Leonardo shook his head and took a few more paces away from Lisa. He had been working on her portrait, layering a pigmented glaze over the painting with obsessive patience. It might take him years to achieve the appearance of inner radiance, but there was no other way to pay tribute to her. The portrait of Lisa occupied his thoughts just as solving the problem of flight did. Maybe the way he was painting her had the power to eclipse the business of portraits to something much bigger, more timeless.

“Is it so easy for you to deny yourself emotion—to feel pain or even love?” She reached out, snatching at the side of his cape. “I look at you, dear Leonardo, and I see a great scientist, an engineer, even a magnificent painter. But what of your emotions? Do you ever write in your many notebooks of your feelings for me, or for Salaì or Beatrice? Or are all your scribblings tributes to your inventions?”

“I’m not a piece of dead wood, signora, if that is what you are suggesting.”

“I know we have shared so much, and you have brought me back to myself. But, your father on his deathbed—”

“Leave me to my thoughts,” he interrupted. “Go back to your friends.” He pulled his cape from her fingers. The failure of his fresco sat heavily in the pit of his stomach, and he cursed the way he had sullied his name.

She hesitated behind him; there was a sweetness in the air: lavender and lilacs. But Lisa turned back to the party.

In the courtyard, he stumbled and, feeling disinclined to walk on, he shook off his cape and lay down on the grass. He felt very hot and thirsty, and was glad to surrender. Exhaustion was a heavy, wonderful blanket. His body sank to the earth.

He allowed himself a memory, something from his childhood: how he trod his pudgy little-boy feet through the forest, brandishing a stick, his warrior sword. Four or five years old he might have been at the time. When he came to the river next to the town of Vinci, he tested its depths, then plunged it into the still waters, triggering a tiny vortex of action. He still remembered the tug of joy when he realized that everything in nature curved—nowhere was there a straight line to be found, not even in his powerful stick.

Adults might aspire to solve wars between the Italian states or build a cathedral with a monumental dome. His aspirations at the time were as small as his tiny hands. He might pick up a stone and hold it, feel its weight, wonder at its round shape. He never thought about time—its significance, the measurement of one minute becoming an hour, becoming a day. He scrambled his way up the boulders, past the meadows that spread wide behind his house and into the forest that shimmered with shadows and promise. He was occupying space, not time. Picking up a rock that seemed to want him, that fit into his hand as a goldfinch might, that he could warm with his touch. He remembered how he would stand still, bare feet nestled in the grasses, listening to the sounds of nature: the alarming birdcalls, the rustling of cypress branches, the groaning of tree trunks. All of it amused him, inspiring him to shout back at the forest: “Buon giorno!”

Other times, he would whisper to his rock friend, tickling it with his voice like a feather. The little stone in the sweaty palm of his hand. That moment of gladness, a tentative conversation, not sure about each other, and then, by the time morning had turned into afternoon, the blossoming of trust.

His mother, Caterina—where was she during those languid days of childhood play? Likely out somewhere in the fields, pulling rocks from the soil, picking lemons, planting olive trees, hoping to find enough food to feed them at night. Even as a little boy, he understood that they could not be together by day. He accepted as fact her daily disappearance. When he woke in the morning, he walked sleepily to the cup of goat’s milk and the bread set out for him on the table. Despite his hunger, he never finished the bread entirely. Maybe he wanted to leave proof that she had been there. Maybe it comforted him somehow.

What was certain was that his mothe

r loved him. When he found her in their stone hut at the end of the day, she would bend down and hug him, and take her shawl from her shoulders and wrap it around both of them, as though they were bandaged together, and he could taste the salt on her neck and breathe the rosemary oil she pressed like melancholy into her thick black hair.

He supposed, on looking back, that he was learning to be patient. Or learning to be a student of the world. When he sat in the apple tree, he watched the cows closely. Their tails would whisk up into the air and slap down hard on their backsides. At first, he thought this was a signal to him. An adult, such as his grandfather, would say he was studying the cows. What he was doing was watching them. One long, languid afternoon, when the cicadas were buzzing so loudly they seemed to be inside his head, he looked closely at the cows. It grew hot and still. He stayed quietly in the branches for the entire afternoon. As the sun dropped low toward the earth and the evening breezes rustled the branches of his apple tree, that’s when he realized the cows were not signaling to him; they were merely flicking the flies off their backs. He felt a hollow loneliness then—and even now, he still felt it as a memory.

An ache in his heart. Leonardo from Vinci—a man without a respectable family lineage or even a last name. He shifted, feeling empty, and he felt sorry for the child with the tiny hands and the bonnet rough and dirty on his head. People liked to believe they would never forget the face of a loved one, but that was not true. Flesh, left unseen, untouched, unloved for long enough, dissolved and floated away like mist. With time, his mother’s soft adolescent face had disappeared entirely from his mind. He remembered thinking how curious it was that he could no longer remember her face, though he was not a callous child. Even the color of her eyes, so young and shot through with a shining faith, faded from black to gray to nothingness. Her figure, thin and muscular, which once held him with such strength, receded into the fog until he could no longer feel her arms.

Memories can hang low in the brain like fish sliding through silt at the bottom of a river. Something surfaced while he was a student apprentice at Verrocchio’s studio. His mother was startled back into existence. He was sculpting small figures from clay: wet the ball of red into something warm and malleable, then pinch it into a perfectly proportioned human being several inches tall before laying the blade of a sculpting knife to the body. It was satisfying work—better than making paintbrushes for the studio or sweeping the floor—but with its own challenges. Try as he might to breathe the fire of his imagination into the form, the clay resisted.

Tuscan Daughter

Tuscan Daughter